An explanation of current thinking on using Nitrites and Nitrates for the home curer.

My aim here is to provide some explanations and a personal view on some of the current issues around this topic. These are issues that I have found confusing with contradictory information available in books and on the internet. No criticism is intended for the confusion, I believe that much of that stems from the changing attitudes, knowledge and legislation associated with processing food and the additives used. I would like to share what I have learned about these issues to help you feel confident that the recipes you are following are safe.

I write this from a UK / EU perspective. I should also be honest about my qualifications here. I don’t have any. I am not a butcher or a chef and I have had no formal training in charcuterie. I have read books, papers and internet forums and believe I have a good understanding of current thinking and EU legislation. I am also a scientist (biologist), so I do have some understanding of the chemistry and microbiology behind some of the issues. Producing your own food has to be your own responsibility; after all, isn’t that part of the point and a great source of the satisfaction in doing it in the first place?

Legislation in the EU

The core principles and provisions of food additives legislation are set out in European Parliament and Council Regulation (EC) No. 1333/2008. This is enforced in the UK through country specific legislation (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) administered via the Food Standards Agency . A food additive is helpfully defined by that regulation as follows:

“any substance not normally consumed as a food in itself and not normally used as a characteristic ingredient of food, whether or not it has nutritive value, the intentional addition of which to food for a technological purpose in the manufacture, processing, preparation, treatment, packaging, transport or storage of such food results, or may be reasonably expected to result, in it or its by-products becoming directly or indirectly a component of such foods” ¹.

The EU also publishes a list of permitted food additives which includes Sodium and Potassium Nitrite and Nitrate ². Strangely, the list does not include salt (Soduim Chloride), I guess salt is “…normally used as a characteristic ingredient of food…” and therefore does not qualify as a food additive.

The health issues

Let’s be clear on this. Eating processed foods, particularly cured foods, is not good for you. There is an increased risk of cancer with the eating of foods cured with Nitrites and Nitrates (referred to as curing salts from now on) ³ ⁴ ⁵ ⁶. Quite simply, the more cured food you eat the higher your risk of developing certain cancers. There is also a well established link between cardiovascular disease and high salt intake ⁷ although the Salt Association in the UK disagrees, saying that the evidence is out of date and inadequate ⁸. I concentrate here on the cancer and curing salts issue and leave the Sodium Chloride debate for another time.

World Heath Organisation announcement October 2015

Lyon, France, 26 October 2015 – 22 scientists of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer agency of the World Health Organization (WHO), got together having evaluated the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat from previously published research ³ ⁴; what I would call a literature review. This is a good thing, because the scientists read the literature, interpret the findings and publish an overall picture with a conclusion so that we don’t have to. It means that as consumers we are better informed. For me, this is the EU working at its best; collaboration between scientists of member states, in this instance 10 countries. Their conclusion was, at first glance, a stark one. Processed meat was classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1), based on evidence demonstrating that in humans the consumption of processed meat causes colorectal cancer. Group 1 also contains tobacco and asbestos. Given that conclusion why would anyone want to be in the same room as a piece of ham, let alone eat it?

Red meat was classified as “probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A)”, this means that currently there is insufficient evidence to draw anything more than a “probably”, they don’t say how probable is probably, because they don’t know, the jury is still out. Group 2A includes substances such as glyphosphate (weed killer) and creosote.

What is processed meat?

The WHO helpfully defines processed meat as that which has been transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking, or other processes intended to improve preservation or enhance flavour ⁶. Just about any meat can be processed. Examples of processed meat include hot dogs (frankfurters), ham, sausages, salami, corned beef and canned meat and meat based preparations and sauces. This is a one size fits all definition covering the whole of the EU and not all sausages are created equal. Sausages in the UK generally do not contain Nitrites / Nitrates, just common salt (Sodium Chloride); whereas sausages from other EU countries (e.g. Poland) may well contain Nitrites / Nitrates. So, if you are concerned about an increased risk of cancer from consumption of Nitrites / Nitrates then you need not worry about eating UK sausages. You may want to be careful with salt and fat content but they are different issues.

Processed meat vs Asbestos

The IARC classifies agents or processes into four groups ⁹: Group 1 – Carcinogenic to humans (currently 118 agents); Group 2A – Probably carcinogenic to humans (currently 75 agents); Group 2B – Possibly carcinogenic to humans (currently 288 agents); Group 3 – Not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans (currently 503 agents) and Group 4 – Probably not carcinogenic to humans (currently 1 agent). Processed meat happens to be in the same category as asbestos and tobacco smoke (Group 1); this does not mean they are all equally as dangerous. The classification is about an assessment of the evidence about an agent being a cause of cancer; the classification says nothing about the assessment of associated risk through exposure or ingestion. The conclusion was that eating processed meat causes colorectal cancer. There was also an “association with” stomach cancer but the evidence for that is not conclusive.

So what is the risk?

According to the most recent estimates by the Global Burden of Disease Project, an independent academic research organization, about 34 000 cancer deaths per year worldwide are attributable to diets high in processed meat. Putting that into the context of other known cancer agents, about 1 million cancer deaths worldwide are attributable to tobacco smoking, about 600,000 due to alcohol consumption and 200,000 attributable to air pollution ⁶. My personal view (which is nothing more than speculation) is that the difference in numbers is probably a reflection of the potency of the cancer agents themselves, the numbers of people eating / smoking / drinking / breathing the agents and the frequency with which that activity occurs. I think we can conclude from this that if you smoke, drink alcohol, live in a polluted environment and eat processed food then, if you wanted to prioritise your actions to reduce your risk, you should give up tobacco and alcohol before you give up that occasional bacon sandwich.

What does “…diet high in processed meat” mean?

The IARC do not define what they mean by high, they say that this is clear for red meat (at more than 200g per person per day) but less clear for processed meat ⁴. Studies they reviewed, however, showed an 18% increase in the risk of developing colorectal cancer per 50g per day of eating processed meat; 50g equates to about two slices of my home made bacon. In other words for each 50g consumed there is an 18% increased risk; the relationship between consumption and risk is linear up to about 140g per day where the curve reaches a plateau ¹⁰. So we can say that 140g or more per day is the worst case and definitely not recommended. Dr Kurt Straif, Head of the IARC Monographs Programme is quoted as saying “For an individual, the risk of developing colorectal cancer because of their consumption of processed meat remains small, but this risk increases with the amount of meat consumed”.

Can we trust the data?

I think the simple answer to that question is yes. The IARC Working Group considered more than 800 studies that investigated associations of more than a dozen types of cancer with the consumption of red meat or processed meat in many countries and populations with diverse diets. The most influential evidence came from large prospective cohort studies conducted over the past 20 years ⁴. A cohort study is where different groups of people are monitored over a period of time where one group will be eating high levels of processed meat and another group low amounts (note not zero). The studies were worldwide and a large amount of data was available. The large amount of data and the consistent associations of colorectal cancer with consumption of processed meat across studies in different populations, make chance, bias, and confounding (where other agents may be the cause of cancer in an individual within the group) unlikely as explanations ⁴.

Why processed meat? What causes the cancer?

This is simply the addition of curing salts to meat as a preservative / flavour / colour enhancer (and the addition of salt). If you look around the internet you will find references to the amount of nitrates in vegetables and some use this to discredit the research saying that you get far more nitrates from a portion of spinach or lettuce than you do from a portion of salami. This is true, however, they are missing the point that it is the action of the curing agents, often together with the type of cooking, on the meat that creates the cancerous agent. Meat is high in proteins, lettuce is not; proteins are made from amino acids which react with the curing agents to produce other compounds. Believe me, I would love to advocate a ban on lettuce, but I don’t think that would be justified.

The other compounds I refer to above are known carcinogenic chemicals, including N-nitroso-compounds (NOC) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) created by reactions between the curing salts and amino acids present in abundance in meat. High-temperature cooking by pan frying, grilling, or barbecuing can produce additional known or suspected carcinogens, including heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAA) and PAH ⁴. These are big names for chemicals that contain ring structures with the atoms of the chemicals bound together in a ring shape. It has been known for decades that such chemicals are likely to be carcinogenic, so it comes as no surprise that cured meat is likely to increase your risk of ingesting cancerous agents. Only now however, has WHO felt that there is sufficient evidence to confirm a direct link between eating processed meat and cancer.

Should I stop eating processed meat?

This has to be a personal decision based on your own attitude to risk and other factors in your life. For me, having studied the reports and press releases associated with this, it is a difficult one and by no means trivial. I like processed meat, I like making it and both making it and eating it makes me a happier person which has to be a benefit to my overall health, but would I really miss it if I gave it up? Probably not and I would find some other hobby to fill my spare time. However, even though I make it I don’t consider that my diet is “high” in processed foods; I probably eat small amounts (50g) of bacon, ham, salami a few times a month, certainly not on a daily basis. Remember also that these studies are cohort studies where the diets and incidence of cancer are compared between different groups of people, where one group has low consumption and the other has high. There is not necessarily a zero intake group. For me, I think that I am in the low (or certainly towards the low end) group and therefore I am not too concerned about the 18% increase per 50g per day statement because I have no intention of increasing my consumption.

I also consider other risks in my life, both cancer related and others. I am physically fit, not overweight, I drink alcohol (probably on the high side of moderate but not daily), I don’t smoke. I live on a busy main road with its associated pollution. I cycle and drive a car. There is a risk that I could die from inhalation of air pollution, road accidents, alcohol related illnesses or some other unknown factor; I consider that processed food consumption is contributing only a small proportion of my overall risk. For now, I intend to continue to consume processed meat, that I have made myself, in moderation (about 50g or less 2 or 3 times per month). Making it myself means that I know how much preservative has gone into it.

Quantity of cure (flavour vs. preservation)

If we accept using curing salts to make the products that we want to eat with the desired flavour and appearance then what levels are safe? There are two sides to this that require balancing.

Firstly, the amount of cure needs to be sufficient to make the food safe from harmful contamination by bacteria, in particular Clostridium botulinum ¹¹. This organism produces a toxin which can kill human beings at a dose of a few nanograms / Kilogram of body weight, where a nanogram is a billionth of a gram. Clostridium botulinum exists widely in our environment, particularly in soil which means that we must be careful with things like herbs from our garden. If I am making sausages or salami I generally use bought dried herbs, rather than from my garden, in the belief that they have been sterilised in some way. Clostridum thrives in anaerobic conditions (no or low oxygen, <2%) and at a pH between 4.6 and 7. The bacteria can form spores which are heat resistant even at 100°c. Nitrites / Nitrates inhibit the growth of Clostridium and therefore reduce the production of toxin; they are very effective at this ¹². Reducing the pH of the food below 4.6 also has an inhibitory effect ¹². Add to that a reduced temperature and things get very difficult for the Clostridium bacteria. However, whilst botulism is a killer, we shouldn’t get too hung up on it, modern hygiene, both in the kitchen and at your butchers, should be good enough to prevent the contamination in the first place; curing salts should be seen as belt and braces rather than a fix for sloppy hygiene; prevention is better than cure! Also bear in mind that the botulinum toxin is itself a protein and therefore cooking (5 minutes above 85°c) can break it down ¹¹. So even if you are unlucky (or careless) enough to have some toxin present, it can be neutralised by cooking; just the toxin mind, not the bacteria which left to its own devices in an unprotected environment it will produce more toxin. Admittedly, this is not much comfort if you have botulism in your salami (which is eaten raw) which is why salami has the additional protection of fermentation to get that pH below 4.6 and make it even more hostile to the Clostridium organism and contains both Nitrites and Nitrates (see below).

Secondly, there are the health risks associated with curing salts as discussed above. Too much is definitely not good for you.

Therefore we need the curing salts to be high enough to prevent the growth of harmful bacteria but at the same time be low enough to minimise the risk of cancer from their ingestion. Between 50 and 150mg/Kg of Nitrite is required to inhibit the growth of Clostridium botulinum; incidentally Nitrate has no effect but does form a reservoir of additional Nitrite for products cured for long periods ¹². The EU food people have recognised this and have published legislation for commercial producers which limits the amount of cure in our processed food. However, the legislation is foggy to say the least; it appears to me to be a compromise aimed at keeping traditional practices viable whilst at the same time protecting the consumer. As a home curer I have no obligation to follow the EU regulations because I have no intention of selling my products. I do however, recognise the issues and look to the regulations for guidance and reassurance on the amount of cure to use. In that respect they are very helpful.

The permitted amounts of cure are measured in two different ways; amount added and residual amount (the amount in the final product that we eat). Amount added for a home curer is relatively easy, we just measure the amount we add and stick to the maximum limits of 150ppm for both Nitrite and Nitrate. Residual amount is more difficult, if not impossible, for home curers as we have no way to test the residual amounts in our finished product; not that I am aware of anyway. Some curers make assumptions on what they think is the likely take up in the meat of the added amounts and therefore assume what the residual amount will be. I think this is an entirely reasonable approach and as long as your added levels are not outrageously different from the expected residual amount I don’t think you will go wrong.

The EU provides limits for curing salts for a variety of traditionally prepared products and for generic products not processed in any recognised traditional way ². The UK Food Standards Agency provides a very good guidance note on how to interpret these EU regulations (appendix 3 deals with curing salts) ¹.

So what are the amounts? There isn’t a simple answer to this; possibly the EU at its worst, creating compromised legislation by committee to keep all member states happy. For example, we can have Wiltshire Ham (a traditional English ham) with a residual amount of Sodium / Potassium Nitrite of 100mg/Kg and Nitrate of 250mg/Kg. However, if I was to commercially produce a ham by a different method than the traditional Wiltshire process, such as cure in the bag, then I would be limited to 150mg/Kg for both Nitrite and Nitrate maximum added amount. This sounds confusing but I think the EU is trying very hard not to destroy those traditional products that we all love whilst at the same time encouraging producers to reduce the amount of curing salts in their products. For me the target I am setting myself when reviewing the recipes I use is to limit the added amount to 150mg/Kg Nitrite for ham and bacon plus 150mg/Kg Nitrate for longer cured products such as Salami and Pancetta.

Impact on my own recipes

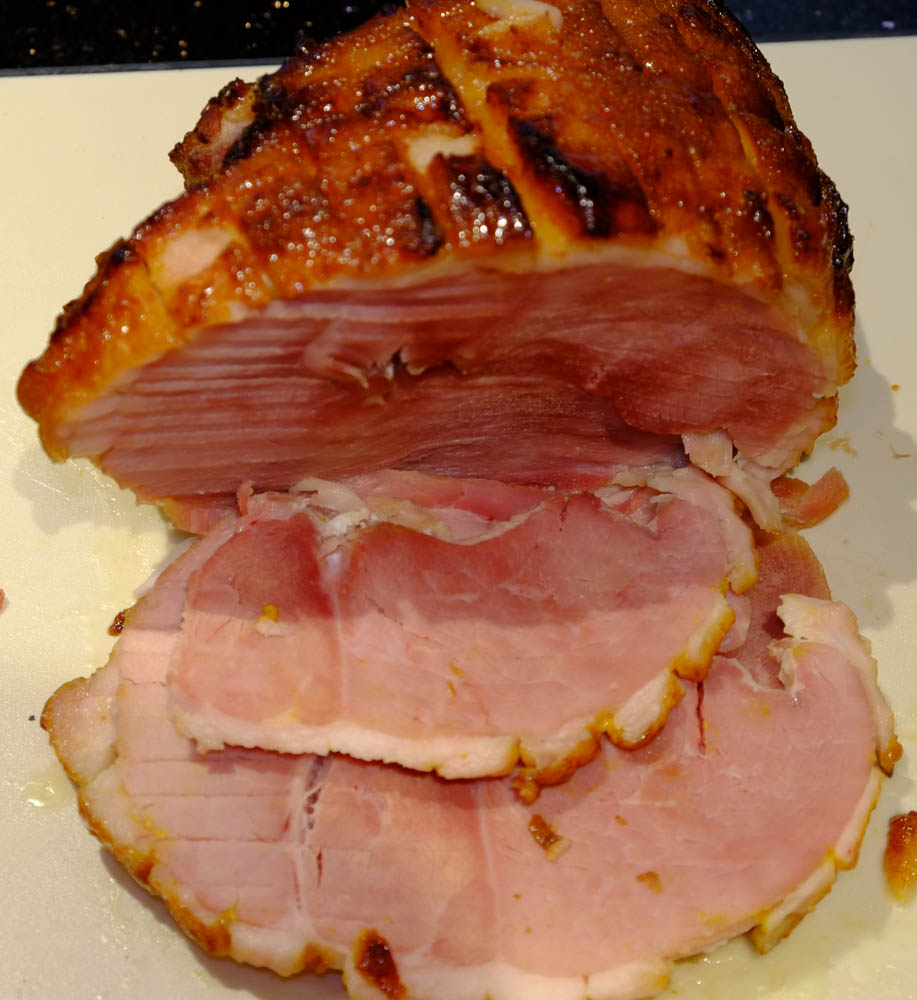

Following my research, for writing the above I have reviewed the recipes I have been using for the past 5 years. My recipes originate from a variety of sources and I have concluded that they are basically sound but that I would like to try and reduce the levels of curing salts in line with the general maximum added amount of 150mg/Kg for both Nitrite and Nitrate. This Christmas (2015) I successfully made “Regulation Ham” using 2.4g/Kg of Cure #2 * as a dry cure in a vacuum bag. This equates to 150mg/Kg Sodium Nitrite and 100mg/Kg Sodium Nitrate. Previously I have used a recipe with 160mg/Kg Nitrite and 300mg/Kg Nitrate. I believe that the source of the original recipe was based on US permitted levels (different from EU levels) and it made assumptions on the likely uptake of the cure by the meat and therefore the likely residual amounts. At 160 / 300mg/Kg it was not far off the current permitted residual levels for Wiltshire Ham assuming less than 100% take up, so I have no concerns over what I have eaten in the past. One anomaly with the original recipe that I cannot immediately reconcile is the level of Nitrate given that this ham will be cured and then immediately cooked and eaten with any left overs being frozen. The only thing that I can think of at the moment is that the curing time of two weeks is rather long and maybe that was the reason for the Nitrate inclusion; or maybe it was just a belt and braces approach by the author. Next time I make a ham I will go for “Regulation Ham number 2” excluding the Nitrate.

Nitrite / Nitrate Free?

There is a school of thought that charcuterie can be successfully made using just salt (Sodium Chloride) e.g. River Cottage Handbook No.13 Curing and Smoking by Steven Lamb. Steven makes a very compelling argument and claims success with just salt at rates of between 2-3% per weight of meat. Whilst researching this article I also discovered that Parma Ham and Spanish Serano ham is also Nitrite free which came as a surprise. I don’t understand, yet, how they can get that deep red colour in the ham without adding Nitrite. However, I intend to try the recipe in Steven Lamb’s book for bacon to see if it does indeed make bacon as I expect bacon to be and I will report back.

Update

I tried a recipe from Steven Lamb’s book, Cider Cured Ham on page 195. It made a very nice product and I enjoyed eating it, however, in my opinion, it was not ham; it was boiled and roasted pork. It was a lot of effort (and expense) to make something that looked and tasted like pork, not ham. I doubt that I will go on to try the bacon recipe.

References

- Food Standards Agency; Food Additives Legislation Guidance to Compliance; July 2014.

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1129/2011 of 11 November 2011 amending Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council by establishing a Union list of food additives.

- IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat; Press release N° 240; 26 October 2015.

- Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat; The Lancet Oncology; October 26th 2015.

- WHO Clarification on IARC Report 29th October 2015.

- WHO Q+A on the Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat; October 2015.

- Action on Salt health factsheet.

- Salt Association position statement.

- IARC Carcinogenic agents classification.

- Doris S. M. Chan et. al. Red and Processed Meat and Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies.

- WHO Botulism Factsheet N0. 270.

- The effects of Nitrites/Nitrates on the Microbiological Safety of Meat Products; The EFSA Journal (2003) 14, 1-31.

- River Cottage Handbook No.13 Curing and Smoking by Steven Lamb.

* Curing salts are sold as Cure #1 (or Prague Powder, or Pink salt) and Cure #2. In the UK Cure #1 contains 6.25% Sodium Nitrite in salt (Sodium Chloride) and cure #2 contains 6.25% Sodium Nitrite and 4% Sodium Nitrate in salt (Sodium Chloride). The proportions are different in the US; wherever you are, check with your supplier and check the levels for your recipe.