What?

To accompany the homemade cheese I make sausages, bacon, salami, ham (English style) and Pancetta all in the comfort of my own kitchen with occasional forays into the garage. I have not bought commercially prepared bacon or sausages for years. I share some of my experiences with charcuterie below.

But why?

This is the same answer I give to the cheese question – because I can and why not? However, there is one important additional point with charcuterie which is that I know exactly what has gone into my processed foods. I have selected the source and cuts of meat and have controlled the processing and additives to my satisfaction from start to finish. I have taken responsibility for ensuring those processed foods are the best that I can have. For me, it’s about knowing where my food has come from and what it’s gone through to get to my plate. It’s also fun to do.

The Alchemy

I enjoy food and cooking and charcuterie is a logical extension to that. I like the transformation of the meat, turning whole pieces, or minced, pork into something completely different with a unique look and flavour. Curing, fermentation and smoking were traditionally developed to enable storage of meat in the absence of refrigeration. The meat from fattened pigs killed in autumn could be preserved for eating throughout the lean winter months. Today, most of us have reliable refrigeration in our homes and these techniques are used only to maintain that unique appearance and flavour from cured foods.

How curing salts work

See also use of Nitrites/Nitrates.

This is a very brief outline of how I think curing salts are working. Salt (Sodium chloride) has an osmotic effect on meat and any contaminating bacteria i.e. it will draw water across cell membranes in the direction of low to high concentrations of salt. As the water moves to an area of high salt concentration so that concentration drops until equilibrium is reached. Bacteria cannot tolerate this withdrawal of water and they will either die or be inhibited. Any meat will become dehydrated, further denying any bacteria to the water they need to survive.

Nitrites in the form of Sodium or Potassium nitrite (Na or K NO₂) breaks down to Nitric Oxide (NO) which reacts with the Heme in myoglobin (the substance making meat pink in its raw state i.e. not blood) forming Nitrosomyoglobin which gives the characteristic pink colour of bacon and ham. Sodium nitrite is also very toxic to humans at relatively low concentrations (I don’t have a figure to hand) which is why we cannot buy it in a raw state but only mixed with table salt in the form of curing salt at a concentration of 6.25% in Europe. Even at these concentrations care needs to be exercised in its use and it must be weighed out very precisely to the nearest 10th of a gram or less.

Nitrates (Na or K NO₃) do not have a significant effect on inhibition of bacteria or on the curing effects on meat but they do provide a reservoir of additional Nitrites as the NO₃ is slowly broken down to NO₂. Again Sodium Nitrate is also toxic to humans but not as toxic as Nitrite, therefore we can buy this in its raw state but again it needs to be used with caution and weighed out accurately to the nearest 10th of a gram or less.

It is not unusual to come across recipes specifying curing salts in teaspoon (or worse) quantities. Personally, I don’t think this is good enough and grams or milligrams per Kg of meat being cured should be specified.

The environment

I don’t live in the Alps where the winters are cold and dry and I don’t have a cellar with a constant year round temperature and humidity. I have to make do and mend with a combination of my garage in winter, my kitchen fridge and a vacuum packer. This means that the making of charcuterie for me is seasonal, which I like. That doesn’t mean that the enjoyment of eating it is seasonal; because I eat little occasionally and can make enough in winter, vacuum pack it and freeze it, to last all year round.

Equipment

I admit it, I like gadgets, especially kitchen gadgets. I have a sausage stuffer, a vacuum packer, a mincer and a large slicing machine. You don’t need all of these but it helps. If you need to prioritise them and you want to make sausages (fresh or salami) and hams then I would say to get the sausage stuffer and mincer first, followed by the vacuum packer and then a slicer. It is possible to make charcuterie without any of these gadgets but you will get a more consistent product and the vacuum packer will help keep your products in pristine condition in the fridge or freezer. Note, I started out with a Moulinex domestic kitchen slicer but I quickly burnt out its motor trying to slice bacon and I eventually invested in a large (probably too large) commercial / small restaurant slicer.

The health issues

Let’s get one thing out of the way, eating processed foods, particularly cured foods, is not good for you; it’s definitely not the healthy option on the menu. There should be no debate over that anymore, the science is well established and the links are proven even if the exact mechanisms are not yet fully understood. High salt intake allegedly leads to increased risks of cardiovascular disease and intake of nitrites/nitrates increases the risk of certain types of cancer. I have tried to explain some of the issues and the current state of knowledge and what this means for the home curer in a separate page here.

One thing to emphasise here is that prevention is better than cure, meaning that you should be scrupulously clean at all times to the point of sterilising all your equipment to avoid any harmful contamination. Personally, I don’t sterilise but I do keep things very clean and disinfect working surfaces before I start using a Dettol surface cleanser.

Saussages

I have made plain, with herbs, tomato, hot and spicy Mexican, chipolatas, fresh Chorizo, venison, lamb, hot dogs; I could go on. There are thousands of recipes available in books and on the internet. There are a few basic “rules” to follow such as all sausages must contain meat, fat, rusk or breadcrumbs, water and salt. Each of these is there for a reason; feel free to vary the quantities from those specified in the recipe but bear in mind the impact it could have on the finished product. The meat speaks for itself. The fat acts as a solvent for flavours, melts during cooking distributing the heat and giving the sausage a succulent texture. The rusk holds the sausage together, it binds the fat and meat and contains the water, without it you risk the sausage falling apart during cooking. The water helps make the mix easier to stuff into the casings and again makes for a succulent product. The salt is there as a seasoning but also as an important preservative.

Of all the ingredients I find that I almost always reduce the amount of salt in recipes but I hardly ever change anything else. I often halve the salt levels because this suits my taste rather than any desire to have a lower salt diet. A lot of recipes originate from commercial producers/butchers who may need their products to be on sale for a few days and so rely on the preservative qualities of salt. Since I make and then eat, or freeze them within 24 hours I don’t need such high salt content – one of the advantages of making your own.

The next essential ingredient is skins. I buy ready spooled skins from Weschenfelders because they come in convenient lengths, not because I like the spooling. In fact, I don’t like the spooling because I find that the skins do not hydrate properly on the inside and then I have problems with the stuffing. I take the skin off the spool and run water from the tap through the entire length to soak it inside and out. One word of advice, although skins will keep for ages (12 months+) packed in salt in the fridge, the fresher they are the easier they are work with.

Bacon

My first foray into curing was to make bacon. I used a ready-made cure called Supracure bought from Weschenfelders. It works fine and will give you authentic bacon. However, I moved away from this approach because I did not know what was in the cure which seemed to defeat the object of me curing my own bacon. A big driver for doing this in the first place was that I wanted a level of control by knowing exactly what was going into my food. After some research on the net, I came across some very helpful people at the Sausage Making.org forum. I used a recipe on there supplied by Oddley, a forum member. I also went on to use and adapt his ham recipe which I will discuss shortly. I am afraid I was/am a very poor forum member because I took away a lot of learning from the site but contributed nothing, sorry guys, maybe this will make up for it.

Having done a lot of research for this article and the related one on current thinking on curing salts in meat I will be changing my curing recipe to one developed by Wheels (or Phil) who is also a forum member and regular contributor. Phil has an excellent website / blog with some great recipes and calculators guiding you through the EU and US regulations. The next bacon I make will be Phils “favourite bacon”.

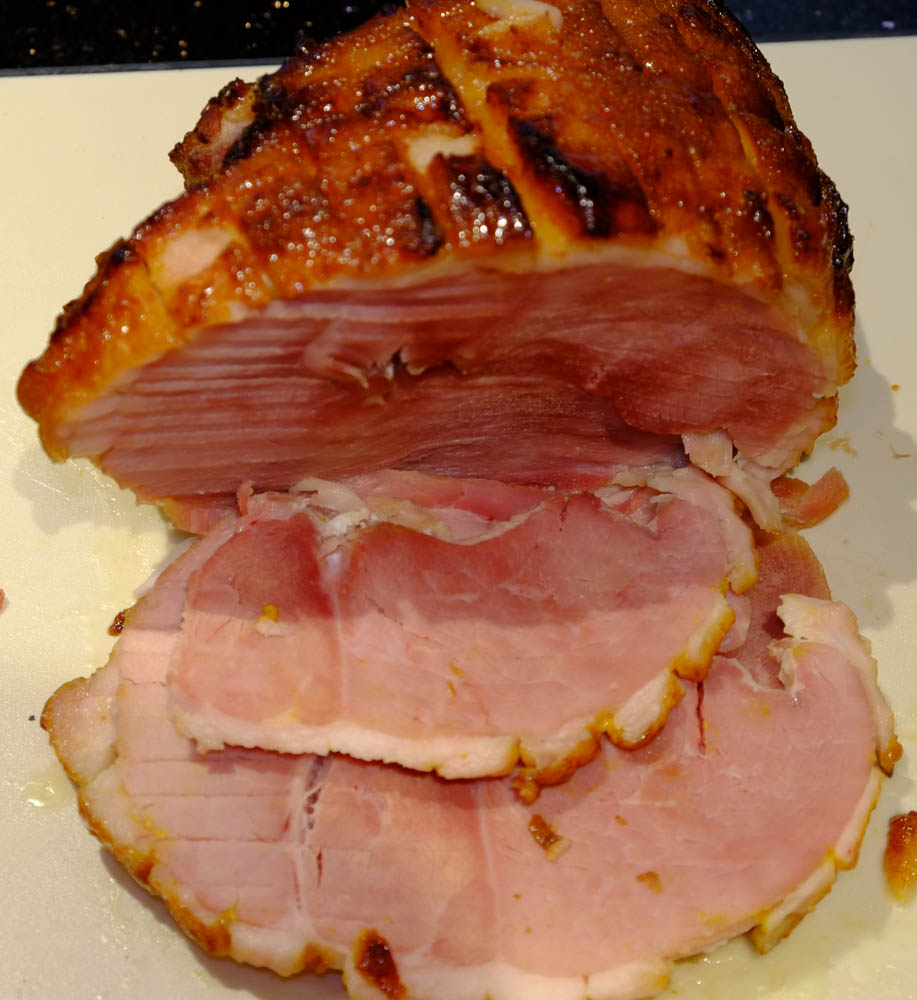

Ham

When I talk about ham, I am talking about the UK version of ham, usually poached (or boiled) and then baked rather than the European air-dried hams. I have made a lot of very nice hams, usually for holiday weekends such as Easter or Christmas. Again, I started off with Oddley’s recipe but have revised it over the years to suit my preferences. This recipe was a combination cure where some of the cure was made into a brine and injected into the meat and some was applied as a dry rub on the outside before packing the whole lot into a vacuum bag and leaving in the bottom of the fridge for a couple of weeks. It worked very well indeed, however since I buy my pork leg as a boned out piece tied up with string (like a few of my other favourite things…) I now untie it and rub the entire cure, as a dry cure, over the inside and outside surfaces before tying it back up with string into a round ham shape.

If you were doing larger pieces with the bone in then injecting would be the way to go. Oddley’s original recipe was based on US standards for the amount of cure, in the absence of any real guidance in the EU. I am now making ham following the EU regulations with 150mg/Kg of added Nitrite and 100mg/Kg Nitrate. I add the Nitrate because of the two week cure time but I intend to try a small ham as an experiment without Nitrate. See here for more on my thinking on that.

There are alternatives to the combination cure such as immersion of the meat in brine/cure solution. Again, I thoroughly recommend Phil’s website for recipes and tutorials. I intend to try Phil’s Cider Ham at some point.

Pancetta

A logical step from bacon and ham is to go for something with a longer cure and a product that resembles those very expensive hams/prosciutto/pancetta that is eaten “raw”. I have used Phil’s recipe for that one, very successfully. In fact, I see that Phil credits the recipe to Jason Molinari, an Italo-American home curer. If I was to make one change I would substitute the brown sugar for white. I feel that the sugar has given it a brown tint which I am not entirely happy with. However, it tastes great and my latest batch is only just ready so I expect it to improve with age.

Drying

It is worth mentioning at this point the drying of cured products. Commercial producers have temperature and humidity controlled cabinets or even entire rooms. Home curers have to be a little inventive and have to monitor the drying product carefully and frequently. I make dried charcuterie on a seasonal basis and I use my garage as a cool (10-15c) hanging area with relative humidity (RH) of 60 – 70%. If the temperature gets too high or the RH creeps into the 80s I retreat to the fridge. The problem with the fridge is that it is too cold and too dry and will dry out the product far too quickly. However, if that happens all is not lost if you have a vacuum packer.

Drying meat too quickly results in a hard crust forming on the outside (so-called “case hardening”) which is not only unpleasant to eat but also forms a barrier to further drying of the meat further in. I find that I can reverse case hardening by putting the meat in a vacuum bag for a few days or up to a week. This draws moisture from the centre and rehydrates the dried out edges.

You could also go as far as Phil and others and build your own drying cabinet. Again, Phil has very kindly and expertly provided instructions for converting a fridge to a curing chamber on his website. For now, I am happy with my small scale production between garage, fridge and vac packer.

Salami

This calls for both curing and fermentation. I found this a little scary when I first tried it because it involves hanging raw, minced pork, albeit inside a skin, in my garage to dry. Whilst my kitchen is spotlessly clean, inevitably my garage is not. Mincing meat greatly increases its surface area and exposes all those tiny surfaces to contamination by bacteria. For that reason, it is extremely important to be scrupulously clean whilst making it and to have confidence in the recipe you are following. As well as adding Nitrite, the cure for Salami also includes Nitrate which is slowly converted to Nitrite over the lengthy curing period. The mixture is also inoculated with a bacterial culture containing mixed strains of Lacto bacillus bacteria; I used Bessastart from Weschenfelders. The bacteria ferment natural lactose in the meat and additional lactose in added milk powder to produce lactic acid lowering the pH (making it more acidic) in the process. Clostridium botulinum is inhibited by a pH below 4.8.

The recipe I have used for Salami has been a Milano salami from the book Charcuterie by Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn. It is flavoured with fennel seeds, garlic, pepper and red wine and is superb. For me, this has been the most successful cured product I have made. I have also made a successful Chorizo from the same book.

Smoking

Traditionally, smoking, like curing was a method of preserving food for storage. Meat would have been hung in the rafters of a smokey room where the rising smoke would have both coated it in a preservative film and dried it. Today the main purpose for smoking is to add flavour, modern tastes (certainly mine) preferring a light smoke rather than the perhaps very heavy smoke of decades ago.

My first introduction to smoking (of meat or fish – anything else is another story) was in the French Alps in late December 1999 / early January 2000. The owner of the hotel we were staying at cured and smoked his own hams. I am talking whole legs of pork, bone-in. He said his curing recipe was a family secret (I am guessing it did not conform to current EU regulations) but he did give us a tour of his smokehouse. This was a simple square building about 2 metres square and 5 metres high made from concrete block with a timber and corrugated tin roof. He simply hung the hams in the rafters and lit a small fire in the centre of the floor beneath. He would let the fire smoulder and each day or so would return and repeat the process. When I asked what source of wood he used I was expecting him to say Oak or Alder foraged from the locality or shavings from French brandy casks but, no, I was given a strange look with the reply “wood”. I genuinely think he used any wood he could get his hands on, twigs, pallets etc. I do not recall the ham tasting particularly smokey but it was delicious.

My smoker is a bit more sophisticated, I use a purpose-built smoker with a smoke generator that creates smoke from little bisquettes of wood. Wood is available in a variety of flavours, my favourites being oak and apple. More recently I have also bought a small ProQ cold smoke generator which burns wood dust very slowly in a simple stainless steel spiral with 100g of dust giving about 10 hours of gentle smoke. If I had my time over again, I would make my own smoke chamber either out of a simple wooden structure or an old fridge and use the ProQ as a generator. That would be much more satisfying than the ready-made solution I went for and it is certainly cheaper to start up and run.

I regularly smoke fish, bacon and I have smoked cheese although I have to say that the cheese is not a taste particularly to my liking.

Recipes and resources

You will find links to recipes in the text and menu above. My advice is to make sure that you are happy with the provenance of any recipe and satisfy yourself that the levels of cure are correct for what you are trying to make. They should comply with the regulations for your country/region.

Books

The books that I have found useful are:

- The Sausage Book by Paul Peacock. A great recipe book for UK style sausages.

- Charcuterie by Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn. This is an American book published in 2005.

- Cured by Lindy Wildsmith. A UK based author. Many recipes across a wide range of ingredients but very little on “curing” with curing salts. Nice to have but not really a charcuterie book.

- Curing and Smoking by Steven Lamb – River Cottage Handbook No.13. Charcuterie without Nitrites / Nitrates. Interesting and some good looking recipes that I will try in due course, starting with the dry-cured bacon and maybe the cider cured ham. However, I would be very nervous about making a salami without curing salts OR any bacterial starter culture; that seems risky, even dangerous, to me.

- Preserved by Nick Sandler and Johnny Acton. This was the book that got me into this. Not a book for those wanting to do traditional charcuterie with curing salts etc but some very useful recipes such as the smoked fish and fresh sausages.

Websites

- Franco’s (famous) sausagemaking .org Supplier of sausage making equipment and ingredients and hosts the sausage making forum which is a great place for help, advice and recipes.

- The forum associated with the website above.

- Local Food Heroes Good resource for recipes and curing calculators based on EU and US regulations. I have learned a lot from this site.

- Weschenfelders Good source of equipment, curing salts and skins. Also hold a monthly competition where you can win equipment (I live in hope).